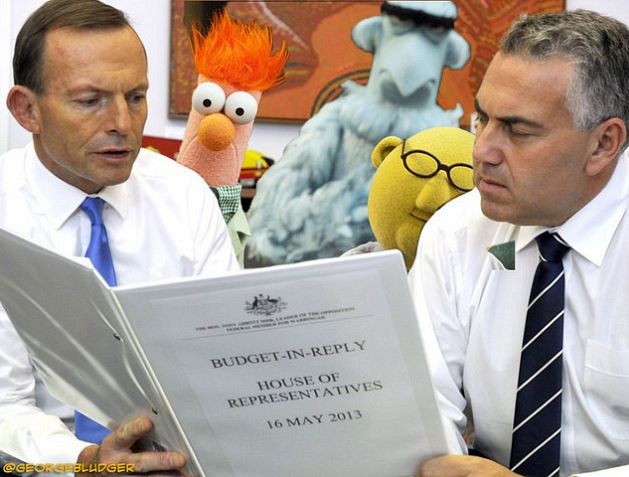

Deficit size fetishism: Why Joe Hockey needs to learn economics

Treasurer Joe Hockey – and many other treasurer's in

developed countries – have a poor grasp of economics,

wrongly conflating national fiscal policy with running a household

budget. UNSW Professor Geoff Harcourt explains (via The Conversation).

THOUGH MONEY AND FINANCIAL FACTORS are integrated in complex ways in

the workings of the economy, ultimately it is real resources – work

forces (sizes and skills), capital goods and natural resources – that

set the upper limit at any moment of time on the size of the community’s

standard of living.

And yet that hasn’t stopped successive Australian Federal treasurers

– along with their counterparts in other advanced capitalist economies

– increasingly using terms which reflect misunderstandings of the role

of fiscal policy in economic policy.

When used by treasurers, phrases such as “we cannot afford it

financially” or “where is the money to come from?” or “you are using

taxpayers’ money”, confuse affairs of the state with what should be left

to the workings of individual households.

Obsessed with the relationship of government expenditure and

taxation, many treasurers suffer from deficit size fetishism, and fall

victim to the “balancing the budget over the cycle” fallacy. Many also

get caught up with hypothecation — matching specific government

expenditures with particular tax sources.

Some confuse the significance of the national debt to income ratio

for the present and future operations of the overall economy, especially

the supposed link between them and the welfare of future generations

relative to the welfare of the present generation. The “we’ll all be

ruined” fear.

Deficit obsession

“Deficit size fetishism” reflects the view that government

expenditure and taxation are always “bad”, regardless of the absolute

sizes and compositions of the two and the overall state of the economy

— for example, the rate of unemployment, the rate of growth, the rate of

inflation (or deflation, as Japan has experienced in recent decades).

Both the sizes and compositions of government expenditure and taxation

need to be assessed by other criteria.

The composition of taxation, the contributions to the whole of

indirect, direct and other forms of taxation, and their incidence on

different groups in the community, ought to reflect equity (fairness)

— such as which groups can least or most afford to pay particular forms

of tax and taxes overall.

The total tax take should reflect the impact required on overall

levels of spending in the economy, these in turn determining the levels

of output, income and employment both prevailing and what the government

would like to see prevail.

Spending and borrowing

The composition of government expenditure is made up, first, of

current expenditures — the salaries of parliamentarians, public servants

and government employees, generally; transfer payments from taxpayers

to recipients of social services, such as unemployment benefits, old-age

pensions and so on; and interest payments to domestic holders of

government bonds.

Secondly, there is government (public) capital expenditures on social

infrastructure — the creation of new railways, roads, hospitals,

schools and so on. Ideally, the level and composition of capital

expenditure should be determined by the perceived medium to long-term

needs of the community for the services they ultimately will provide.

As these expenditures have a significant impact on the efficiency and

productivity of the nation, there is no reason why they should not be

financed at least in part by borrowing, even by borrowing from overseas.

The latter does entail a real burden because interest and principal

repayments mean higher levels than otherwise of exports to service them

would be required. Nevertheless, if the borrowings are used wisely, this

burden may be met and the economy still be better off than it otherwise

would have been.

There is no equivalent burden associated with internal debt (owed to

lenders within the country) for, as noted, this involves a transfer from

taxes to interest payments. The impact on overall demand depends upon

the differences in the consumption and saving behaviour between

taxpayers, on the one hand, and interest receivers, on the other. They

may, of course, overlap. Any fairness considerations associated with

such transfers may be tackled through the composition of the structure

of tax rates.

So government expenditure and taxation, especially taken in

isolation, are not interesting numbers. Certainly not numbers to have a

fetish about, even if you are not just an ordinary Joe, or an earthbound

Swan, or a surplus lover Costello that hands out tax cuts to friends.

The criterion of balancing the budget over the cycle – or,

preferably, creating a surplus – is based on a fallacy that the economy

is not growing, that it will remain at the same level of activity

forever. At least since the 1940s, it has been known that if economies

on average grow from cycle to cycle. Thus, it is possible always to have

deficits (within reasonable limits) without annual deficits exploding;

for specific rates of growth, the deficit approaches particular limiting

values that are livable within a wide range of values.

The real tax and spending relationship

One outcome of this discussion is that hypothecation is a fallacy —

particular forms and amounts of taxes should not be attached to

particular forms of expenditure.

Citizens should pay taxes according to their overall ability to pay

and they should receive government payments according to their

particular characteristics as citizens — unemployed, aged, disabled and

so on. The total of these government expenditures will be financed from

the total funds raised by taxation and borrowing.

“Treasurer Speak” in recent decades reflects serious conceptual

misunderstandings of how economies work and how the functions of the

state should be integrated with the workings of the private sector.

The end result has been the use of scare tactics over a wide range of

issues, tactics which have no foundation in proper economic logic.

Geoff Harcourt is a member of the ALP. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Geoff Harcourt is a member of the ALP. This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

No comments:

Post a Comment